The Emperor will turn 80 late this year. Next January will mark a quarter century since his accession to the Chrysanthemum throne.

The Emperor will turn 80 late this year. Next January will mark a quarter century since his accession to the Chrysanthemum throne.

The Emperor was enthroned as “the symbol of the State” under the current Constitution, becoming the first head of the Imperial family in its 1,300-year history to assume that position from the beginning of his reign. The Emperor has since joined hands with his wife the Empress, who is 78, in exploring the proper status of a national symbol in a democracy.

This country has experienced a number of unfortunate events during the Emperor’s reign—most significantly the Great East Japan Earthquake, the disaster at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant and prolonged economic slumps. In the wake of the 2011 catastrophic earthquake, the Imperial couple visited disaster-stricken areas to offer words of encouragement to local residents. The Emperor and the Empress have also continued to pray that our nation will never again be visited by the ravages of war. By doing all this, the Imperial couple have established an image of how the Emperor should conduct himself as the symbol of the state—namely, his obligation to place himself at the service of the people.

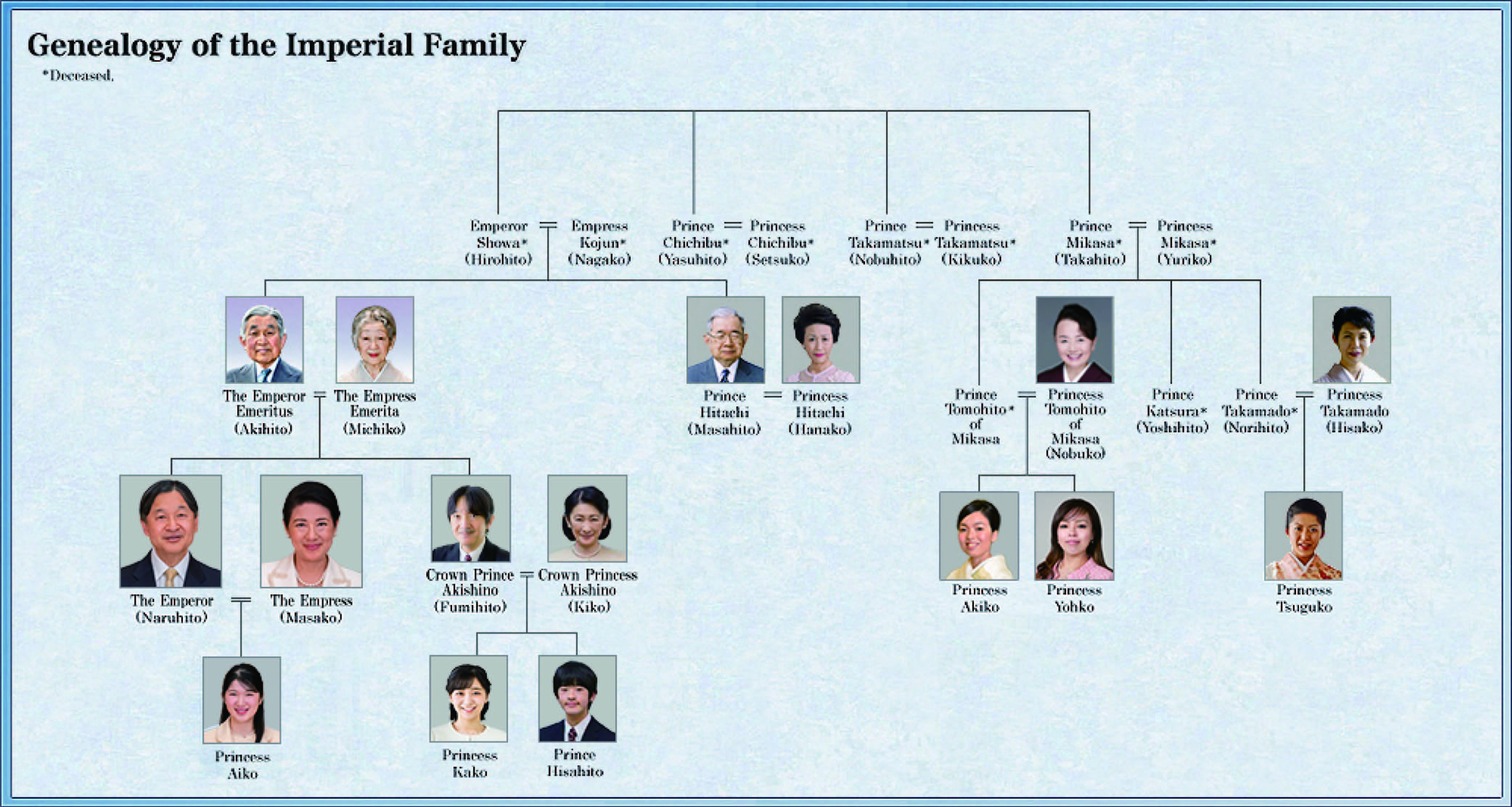

As circumstances stand today, however, the Imperial family is at risk of dying out. The family has 22 members, six of whom are eligible to ascend to the Imperial throne. Three of the six are direct descendents of the Emperor: his two sons and his grandson.

Point 1: The Emperor is distinct from Emperor Showa in that he was enthroned as the symbol of the state under the Constitution, while Emperor Showa was regarded as a living god during and before World War II, but defined as the symbol of the nation under the postwar Constitution.

The Emperor’s position as a symbol of the unity of the people is expressed through his active and continual dedication to the people as well as his constant prayers for their well-being and peace.

The Imperial Household Agency will soon announce the main points of a plan regarding the funeral rites to be performed for the Emperor and the Empress and mausoleums to be built for the Imperial couple. Although both the Emperor and the Empress have some physical ailments, the couple enjoy generally good health. The agency’s announcement of changes in the burial procedures while the Imperial couple are alive would have been unthinkable in previous years.

Simplicity is the watchword for the new funeral rites. In April last year, the Emperor and the Empress announced their wishes concerning the matter, and the agency started studying specific plans in line with their feelings. One major point is to abandon the Imperial family’s tradition of being buried, a practice that has been observed since the early part of the Edo period (1603-1867). Instead, the plans call for cremation for the first time in 400 years, and reducing the scale of their funerals and mausoleums.

In Japan, the dead are usually cremated, and many couples choose to be interred together. The agency’s decisions about the Imperial couple’s funerals, including reducing the size of their mausoleums, are intended to accommodate their wish to minimize the impact of the rituals on the economy and other aspects of the people’s lives.

The agency’s latest decision about the Imperial couple’s funeral procedures, as well as the announcement of the decision, were based on their wishes. This indicates the Imperial couple’s clear determination to honor the traditions of the Imperial family, but also change what they believe should be reformed within the limits of their abilities.

On March 16, 2011, five days after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Emperor issued an emergency video message to victims of the calamity and other members of the public through NHK. The message reflected the Emperor’s belief that issuing such a message is one of the duties he must fulfill as the symbol of the state.

The video message was also intended to express the Imperial couple’s determination to “give our heart to the victims and disaster-stricken people and serve them for a long time,” said Yutaka Kawashima, grand chamberlain of the Imperial Household Agency.

Some people compared the Emperor’s unusual message to the radio broadcast on Aug. 15, 1945, of Emperor Showa’s announcement that Japan would accept the Potsdam Proclamation and surrender to the Allies in World War II.

The Emperor’s message and Emperor Showa’s announcement are entirely different in both substance and circumstances. Still, the two messages may resemble each other in that both were direct appeals to members of the public, urging them to confront a national crisis.

In 1989, the current Emperor ascended to the throne as the symbol of the state, as dictated by the Constitution. This was in contrast to Emperor Showa’s accession to that status, which took place on the strength of the Constitution promulgated in 1946 and enforced in the following year, prior to which he had reigned under the now-defunct Meiji Constitution, which was promulgated in 1889.

The Emperor wears various hats—one as the head of the 1,300-year-old Imperial family, another as the chief administrator of Imperial rituals, a third as a gentle yet strict father, and others as a devoted husband and a scientist. However, the Emperor’s basic thinking and behavior are based on his desire to adhere to the Constitution. He is confident of his duty to proceed hand in hand with the Empress in serving the country and the people, and act in accordance with that principle.

In June 2012, Shingo Haketa, former grand steward of the Imperial Household Agency, spoke about the Emperor’s feelings regarding his position. “The Emperor is actively devoted [to fulfilling his duty], in the firm belief that his status as the symbol of the state is inseparable from his activities based on that position and that conducting activities is indispensable for his status as the symbol of the state.”

Haketa’s remark rings true to this writer, who has had sufficient opportunity to closely observe the Emperor’s activities.

The Imperial system does not permit abdication. Although he will soon turn 80, the Emperor follows a vigorous daily schedule of work that even young people would find hard, after undergoing prostate removal surgery and a heart bypass several years ago.

The Emperor has previously described his relationship with the people by saying both “stay close to each other.” At a press conference marking his birthday in 1998, however, the Emperor said his duty was to “serve the country and the people.” Makoto Watanabe, then grand chamberlain of the agency, said the remark was intended to convey that the Emperor’s duty is marked by “activeness.”

One aspect of the Emperor’s duty to serve the country is his promotion of international goodwill. The Imperial family distances itself from the government’s diplomatic activities, which could be deemed as a form of political action. Over the years, the Imperial family has adhered to this principle, interacting in the same way with all countries, large or small. After meeting the Emperor and the Empress, most foreign dignitaries find they have become admirers of the Imperial couple.

Both the Emperor and the Empress are knowledgeable about various aspects of the world. Before meeting foreign guests, they study to gain further knowledge. On some occasions, the couple can speak about little-known parts of the historical relationship between Japan and the countries to which their foreign guests belong. For instance, no foreign dignitary could resist being charmed by the Emperor and the Empress if they expressed gratitude to him for his country’s rescue of a wrecked Japanese ship several hundred years ago.

The Empress frequently states that friendly ties between two nations start from person-to-person relationships. The Imperial couple’s cordial hospitality has done much to increase the number of foreign enthusiasts of Japan, thus serving as what may be called a guarantee of security for our country.

Point 2: Given the current membership of the Imperial family and the Imperial House Law, the Imperial family is at great risk of ceasing to exist one day. The Emperor and other members of the Imperial family have a strong sense of crisis on this point.

Prince William, who is second in line to the British throne, and his wife Katherine, Duchess of Cambridge, on July 22 welcomed their son Prince George, a great-grandson of Queen Elizabeth. As Britain recently revised its royal succession laws, first-born children take precedence in the line of succession, regardless of their gender. Prince George is third in line to the British throne, a position he would have held even if he had been female.

In constrast, under Japanese law, women born into the Imperial family are not in line for the chrysanthemum throne, let alone those who become princesses by marrying an Imperial family member. The Constitution stipulates that “The Imperial throne shall be dynastic,” but does not refer to gender. However, according to the Imperial House Law, which applies to Imperial family members and was handled in line with the Constitution of the Japanese Empire before the war, the person ascending to the Imperial throne must be a male descendant of the Emperor through a line of males. The eldest son in the direct line has precedence in order of succession, the law says.

Biologically, however, this system cannot be sustained without the use of concubines or adoption. Needless to say, the concubine system is intolerable in a democratic nation and was abolished at the time of Emperor Taisho. The law also prohibits the adoption of sons.

The crisis regarding the Imperial throne is clear just by looking at the current Imperial family tree. The Emperor’s sons, Crown Prince Naruhito and Prince Akishino, are two of six heirs to the throne. Prince Hisahito, the son of Prince Akishino, is the only heir among the Emperor’s grandchildren. There are currently eight princesses who were born into the Imperial family, but they are not entitled to succeed to the throne and will become ordinary citizens upon getting married.

The notion of a “symbolic emperor based on his activities,” which is the philosophy of the Emperor, and the idea in the Constitution of the Emperor as “deriving his position from the will of the people with whom sovereign power resides” are inextricably linked. Other Imperial household members are engaged in various official duties in support of the Emperor and Empress. However, these supporting members may dwindle away or disappear in the era belonging to the generation of the Emperor’s grandchildren.

The patriarchal system was legally abolished in Japan after the war, but it remains in the Imperial household system. The Emperor’s opinions are thus supposed to be reflected in the rules governing the Imperial family. However, the Imperial House Law is a law of the state, which should be revised in the Diet.

Above all, the Constitution states that the Emperor “shall not have powers related to government.” Based on this rule, Imperial Household Agency Grand Chamberlain Yutaka Kawashima explained in a 2011 lecture: “As he shall not have powers related to the government, is it expected that [the Emperor] shall not be interested in circumstances of the state? This is totally wrong. He will not take either side of conflicting opinions on a certain subject. He will not express support of any opinion in such a case. In other words, he will not participate in a game of obtaining 51 percent of the support in any matter.”

The Imperial House Law defines the rules for the Imperial family and is at the same time state law. The Emperor and other Imperial family members thus cannot openly say that they want the current system to be changed, even if they face a crisis in which the very existence of the family is in danger.

Suffice it to say, the Emperor is deeply concerned about the crisis of the Imperial family.

Point 3: Recent years have seen two proposals to revise the Imperial House Law. One urged the acceptance of empresses regnant and matrilineal emperors to maintain the Imperial family. This idea was shelved after Prince Hisahito, a grandson of the Emperor and third in line to the throne, was born in September 2006. Another reason the proposal was shelved was opposition to the idea of an empress regnant.

The other proposal was a revision of the Imperial House Law that would allow female members of the Imperial family to retain their Imperial status after marriage to prevent a decline in the number of Imperial family members.

An expert panel on the Imperial House Law was established in 2004 as a private advisory organ to then Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. At that time, the Imperial family faced a crisis because no prince had been born since the birth more than 40 years earlier of Prince Akishino.

The panel concluded that priority in order of succession should be given to the emperor’s firstborn child, regardless of sex, and called for opening the way for the emergence of empresses regnant and matrilineal emperors. If an empress regnant’s son or daughter ascended the throne, he or she would be defined as a matrilineal monarch. The panel also called for allowing female Imperial family members to retain their Imperial status after marriage because otherwise the enthronement of an empress regnant might become impossible.

If the Imperial House Law had been revised based on the panel’s conclusion, Princess Aiko, the daughter of the crown prince and princess, would have become second in line to the throne.

There have been eight empresses regnant in Japanese history. But there have been no matrilineal emperors. Some conservatives strongly criticized the idea of a matrilineal emperor. As it turned out, Princess Akishino became pregnant and gave birth to a baby boy later named Prince Hisahito. This secured the line of succession through the Emperor’s grandchild, thereby putting discussions on revision of the Imperial House Law on the back burner.

But if no son is born to Prince Hisahito in the future, the patralineal Imperial line will come to an end. The Imperial Household Agency asked the government in November 2011 to look into the possibility of revising the system to allow female Imperial family members to retain Imperial status after marriage. This was proposed out of concern that if all female Imperial family members married under the current system, Prince Hisahito would become almost the only Imperial family member not on the throne.

In October 2012, the government presented a report containing a list of issues raised by the panel of experts set up in 2004 and some related proposals, including possible amendment of the Imperial House Law that would allow princesses to retain Imperial status after marriage. Another proposal urged that royal status be granted to the spouses and children of princesses, but another proposal sought to disallow that. Imperial status would be limited to Princess Aiko, Princess Mako and Princess Kako, all direct descendants of the Emperor. Whether other female royal family members would remain in the royal family would be left up to them.

But discussions of these issues were dropped after the inauguration of the administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who opposes the idea of an empress regnant or a matrilineal emperor.

Another proposal was to grant Imperial status to the male descendants of 11 royal family members who gave up their status 66 years ago in 1947. But because they were all born commoners and their wishes regarding Imperial status are unknown, it would be hard to obtain public understanding of this proposal.

The future of the imperial family

The U.S. movie “Emperor” (Japanese title: “Shusen no Empera”) is a hit with the Japanese public. Although it is not always historically accurate, it is still interesting as it describes how Americans and Japanese viewed Emperor Showa in those days. Making the emperor a symbol of the unity of the Japanese people has been beneficial not only to both countries but also to the rest of the world.

However, if the current Constitution, drafted under the initiative of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces, had retained a provision of the previous Constitution of the Japanese Empire specifying that the person ascending the Imperial throne must be a male and a direct descendant from the Emperor through the male line, succession would have been even more challenging because the current Constitution is difficult to revise.

The current Imperial House Law was enacted hastily and can be revised with majority votes in both houses of the Diet. If revisions to the law to stabilize the succession of the Imperial family are postponed further, I think it would be tantamount to permanently closing the only way left for the Japanese people to decide the future of the Imperial family by themselves.